NOTE This post is adapted from my book .NET MAUI in Action, available now!

In .NET MAUI, the handler architecture provides a way for developers to access properties of native platform controls. With this you can customise the out-of-the-box controls that .NET MAUI provides, or create your own. Handlers are a lot simpler and a lot more flexible than the renderer technology from Xamarin.Forms, but with this flexibility comes potential confusion about where to implement them and where to keep them. You are free to use whatever approach works best for you, but I’ve come up with some rules that help me manage them in a maintainable way.

Understanding handlers

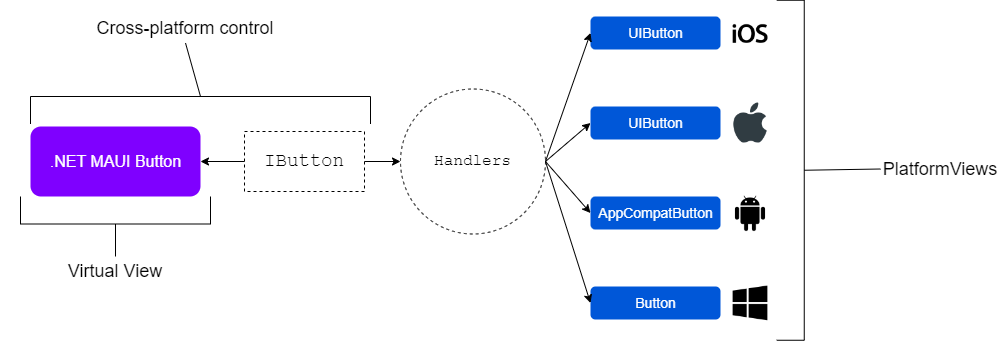

.NET MAUI is more than a UI; it’s a collection of loosely coupled abstractions spanning the UI layer all the way down to platform runtime level. If you wanted, you could implement your own UI layer using the abstractions .NET MAUI provides (in fact, there are some frameworks that do exactly this), but .NET MAUI already provides a UI layer using these abstractions, and it’s handlers that map these abstractions to platform implementations. The following figure shows a simplified view of this architecture fore a Button control.

A

A Button in .NET MAUI is a virtual view that implements the IButton interface. Handlers map that abstraction to specific platform implementations.

The handlers give you access to the native platform views, and you can use them to customise the controls provided by .NET MAUI, or implement your own. By exposing .NET abstractions of the native platform view APIs, handlers provide an easy, discoverable way (through Intellisense) go beyond the (in fairness, quite extensive) styling options offered by .NET MAUI.

When and how handler logic is executed

Handlers define mappings in a dictionary that describe how the cross-platform properties of controls are applied on each platform. For example, a Button in .NET MAUI has several properties that we can modify, including BackgroundColor. A handler maps the .NET MAUI BackgroundColor property, which is of type Microsoft.Maui.Graphics.Color to the platform-specific property, which, on iOS and macOS for example, is of type UIKit.UIColor. .NET MAUI provides three approaches to customising the mapping dictionary: prepend, modify, and append. These let you specify mapping logic in a specific order, so you can specify that your mappings should be applied first (prepend), which will then be overwritten by any default mapping; you can modify the default mappings (note that this requires extensive knowledge of the default mappings), or you can specify that your mappings are applied last (append), which will override the defaults.

It’s unlikely you will ever need to use prepend or modify, so the rest of this post assumes we are discussing appending to mappings. An important thing to remember is that, once executed, your handler modifications will apply to all instances of the control throughout the app, and where you put your handler logic determines when that logic gets executed. For example, if you put it in MauiProgram, it will be executed before any views are rendered, and the modifications will apply to all instances of the view as soon as the app starts. If you put it somewhere else, it will be executed once that code path is reached, at which point all instances of the control the handler is responsible for will be modified.

Let’s consider the following example:

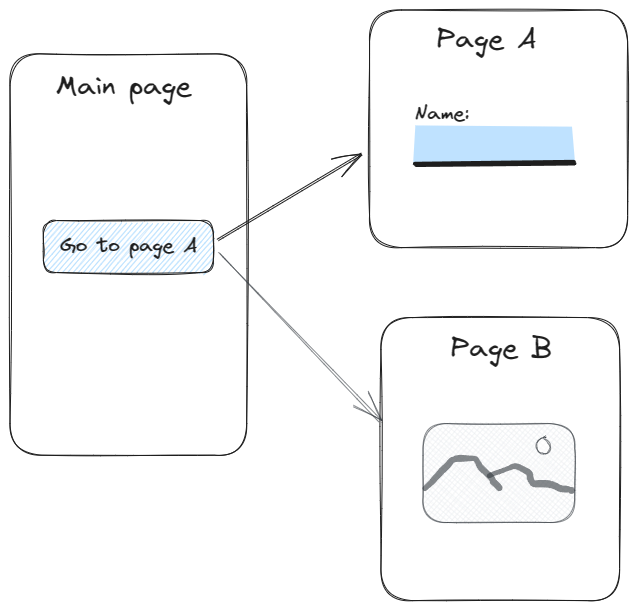

An app consisting of a main page and two sub-pages. One of the sub-pages has a customised

An app consisting of a main page and two sub-pages. One of the sub-pages has a customised Entry control.

Page A has a customised Entry control that implements one of the Material styles. We could build out all of the styling for the custom Entry using pure .NET MAUI, but first we would have to get rid of the border and background of the default control. We could do this with a handler mapping:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Microsoft.Maui.Handlers.EntryHandler.Mapper.AppendToMapping("RemoveBorder", (handler, view) =>

{

#if ANDROID

handler.PlatformView.Background = null;

handler.PlatformView.SetBackgroundColor(Android.Graphics.Color.Transparent);

#elif WINDOWS

handler.PlatformView.BorderThickness = new Microsoft.UI.Xaml.Thickness(0);

handler.PlatformView.Background = null;

handler.PlatformView.FocusVisualMargin = new Microsoft.UI.Xaml.Thickness(0);

#elif IOS || MACCATALYST

handler.PlatformView.BackgroundColor = UIKit.UIColor.Clear;

handler.PlatformView.Layer.BorderWidth = 0;

handler.PlatformView.BorderStyle = UIKit.UITextBorderStyle.None;

#endif

});

In this code, I’m calling the AppendToMapping method on the EntryHandler’s Mapper property. I’m adding a mapping with a key of RemoveBorder (as this is using append, the key can be whatever you like; for modify you would need to know the key to modify). I’m then using a preprocessor directive to set properties of the platform specific views.

Where we put this code matters; your code path has to actually reach this code in order to execute this mapping customisation. So, for example, let’s say we put this in the constructor for Page B. If the user opens the app and navigates to Page A, the Entry will still have the default border. Then, if they navigate to Page B, this code will execute, and the next time they navigate to Page A, the border will be gone. So in this case, it obviously makes more sense for the handler modification to be in the constructor of Page A than it does of Page B.

But there’s another important concept here - once a handler modification is executed, it will apply to all instances of the control throughout your running app. Let’s consider another example:

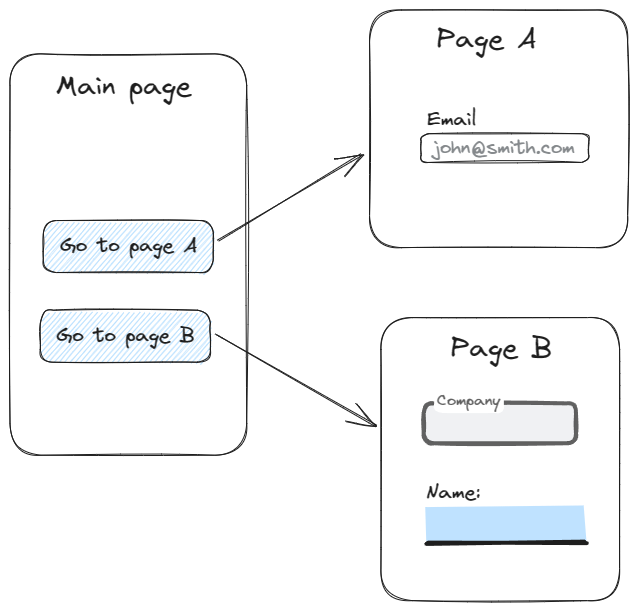

An app consisting of a main page and two sub-pages. One of the sub-pages has a default

An app consisting of a main page and two sub-pages. One of the sub-pages has a default Entry control, and the other has two customised Entry controls.

In this example, Page A has a default Entry control, and Page B has two customised Entry controls, each implementing a different Material style. In this case, we could still put the handler modification in Page B’s constructor; however, once the user navigates to Page B, all entry controls throughout the app will lose their borders, so if the user then navigates back to Page A, they see a weird borderless control without our other customisations (note these other customisations are not shown here, but they would be wrapped in a different .NET MAUI view - you can see more about this approach in my video here).

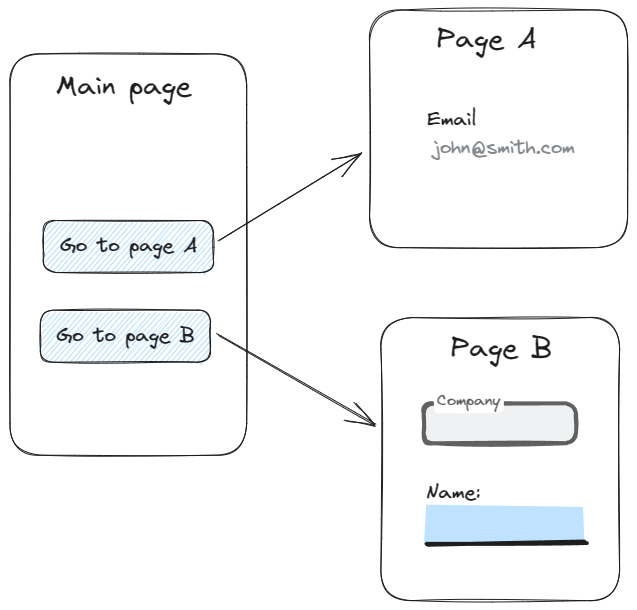

Once the handler modification is executed, all instances of the control are affected.

Once the handler modification is executed, all instances of the control are affected.

There is a relatively simple way to deal with this, if you don’t want your customisation to apply to all instances of a control, and that is to sub-class the control and only apply the modifications to instances of the sub-class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Microsoft.Maui.Handlers.EntryHandler.Mapper.AppendToMapping("RemoveBorder", (handler, view) =>

{

if (view is BorderlessEntry)

{

#if ANDROID

handler.PlatformView.Background = null;

handler.PlatformView.SetBackgroundColor(Android.Graphics.Color.Transparent);

#elif WINDOWS

handler.PlatformView.BorderThickness = new Microsoft.UI.Xaml.Thickness(0);

handler.PlatformView.Background = null;

handler.PlatformView.FocusVisualMargin = new Microsoft.UI.Xaml.Thickness(0);

#elif IOS || MACCATALYST

handler.PlatformView.BackgroundColor = UIKit.UIColor.Clear;

handler.PlatformView.Layer.BorderWidth = 0;

handler.PlatformView.BorderStyle = UIKit.UITextBorderStyle.None;

#endif

}

});

In this example, BorderlessEntry is simply a sub-class of Entry. Whether you sub-class or not (as you may in fact want to override every instance of a control; that’s pretty common), you still need to decide where to put your handler mapping modifications.

Where to keep your mappings

You can implement your handler mappings wherever you like, but there are three specific places where it makes sense, and each one has a different use case.

In the example above, I mentioned putting them in page constructors, but this is not practical or sensible, and you should not do this!.

Here I discuss each of these three locations, and their specific use cases.

App startup

One common approach is to implement handler mappings in MauiProgram as part of the app’s startup logic. If I want to alter all instances of a control, I call the handler mappings in MauiProgram. Depending on how many you have, you can write the code directly in the MauiProgram.cs file in the CreateMauiApp() method, although if you have a lot of modifications, it would make sense to move these to one or more other files, and call them via extension methods.

You can decide what works best for you/your team and the project, but my approach is to create a folder called Handlers in my .NET MAUI project, and I typically have one file in here with one extension method that contains all my handler logic. If it becomes too unwieldy I split it out into separate files within this folder.

Platform folders

Another approach is to put the handler logic in the relevant platform folders. This is the approach I use if I want to modify a control on one platform only, but you could still combine this with the above approach and organise your handler modifications into the platform folders, and still call the extension method(s) during startup. You can even use the same extension method name (or names, if you want to separate by control rather than by platform) and call it in MauiProgram; the specific platform implementations from each folder do not end up in each other’s builds.

Sub-class constructors

Another approach (and my preferred approach), is to keep the handler mapping with the control that we are modifying. If you don’t want to apply a modification to all instances of a control (or even if you do - it can be cleaner to use a sub-class rather than the default class when modifying), you can subclass it and check within your handler logic whether the affected view is an instance of the base class or of your subclass (as shown in the code above).

With a sub-classed control, my preferred approach is to keep the handler mappings in the subclass constructor. This ensures that any time an instance of my control is rendered, the handler logic will be executed, and it keeps all the UI logic for the custom control in one place.

Conclusion

.NET MAUI is fairly non-prescriptive. There are other UI frameworks that are opinionated about how to do a lot of things, but .NET MAUI provides the freedom to find the best way that works for you. This can be a double-edged sword (think asynchronous page initialisation - don’t get me started!), but in the case of handlers I find there are different approaches that are well-suited to different scenarios. Using the three rules above, I can implement my handler modifications in a way that makes sense for how and when they are executed, and keeps them easily maintainable.

Where do you implement your handler logic, and when do you execute it? If you think these rules are valuable, let me know. And, of course, if yours are better, I want to know about that too!